On this special edition of Missouri Farm Bureau’s Digging In, we discuss Amendment 1, or, as the proponents of the measure call it, Clean Missouri. We sit down with Director of State Legislative Affairs B.J. Tanksley and talk through some of the common questions that we have received regarding this controversial amendment:

- What is in Amendment 1 other than redistricting?

- Why do you think these ethics reforms are weak?

- Who gets to decide how the districts are drawn?

- Wouldn’t this get rid of existing gerrymandering?

- How will Amendment 1 silence rural voices?

- What are the constitutional issues with Amendment 1?

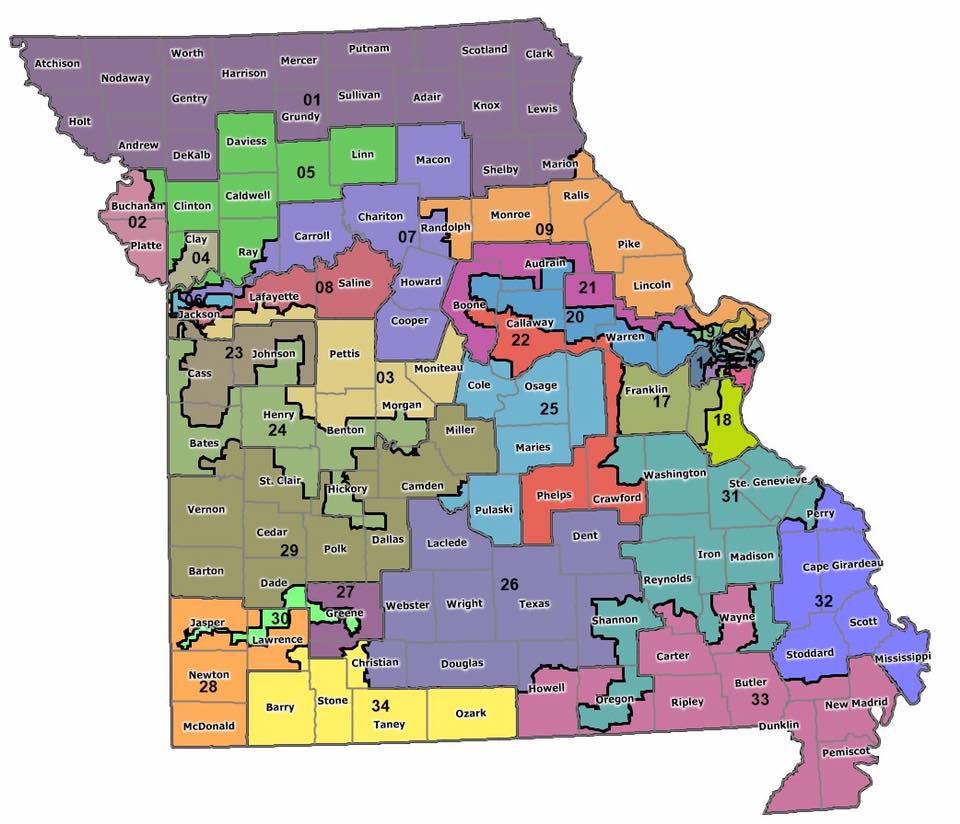

Example Map Drawn for Competitiveness:

Eric: [00:01:25] Hey everybody. I’m Eric Bohl, Director of Public Affairs here at Missouri Farm Bureau and this is B.J. Tanksley, our Director of State Legislative Programs. Today we’re going to be going through the Amendment 1 to the Missouri Constitution that’s on the ballot coming up here in a few days on Tuesday, November 6th. We’ve gotten a lot of questions about some of the details of what is actually in the proposal and it’s a very large proposal. We wanted to take some time to go through those line by line so that you know what’s in it and what we think is a good idea, what we oppose and why.

Eric: [00:01:58] So B.J,. why don’t we just start off by going over a little bit about what is in Amendment 1 and what some of those parts are that are different than what the redistricting proposal is that we’ve really been most vocal about.

B.J.: [00:02:11] You know it’s a good point that time of year where people are starting to actually say okay beyond the candidates what are we getting ready to vote on. Let’s dive into it a little bit. Amendment 1 has several different provisions. We’ve talked a lot about the redistricting and we’ll dive into that again. There are other provisions to it. It starts out by lowering campaign contribution limits for state legislative candidates. It eliminates almost all lobbyist gifts for the General Assembly. It prohibits fundraising on state property, requires politicians to wait two years before becoming lobbyists, and requires that all legislative records be open to the public. All of these sound like great things.

Eric: [00:02:48] And actually all of these are most all of them are things that Farm Bureau has supported in some form of some degree.

Eric: [00:02:56] These are all in our policy book as things that we generally are in favor of these types of reforms.

B.J.: [00:03:01] And to some extent there’s already policy to that effect or we’ve supported some form of this type of reform in the past. It’s just a measure of what are these changes and how far do they go with this measure.

Eric: [00:03:15] And on that note we’ll get into the specifics of each of these, so the first one which has caught a lot of attention actually is that it would lower campaign contribution limits for state legislative candidates. Some people have I think overblown that and said this is going to get all the money out of politics and make it so that is not an issue anymore. Why is that not the case?

B.J.: [00:03:37] It’s really not true at all. When you look at the lowering campaign contribution limits, the current campaign contribution limit is $2,600 per election per candidate. This would lower to $2,500 for Senate candidates. So, a $100 change in $2,000 for state House candidates — you’re just not seeing much change there. And what’s hidden in there is a cost of living adjustment for this. Within just a few years these campaign contributions would be right back where they are now. It looks like this is a change to be able to say you’re changing. I realize it’s a talking point that gets a lot of people’s attention. We get tired of seeing the ads and the mailers and all that and we get that dirty money out of politics altogether. Unfortunately, this doesn’t achieve that goal. It’s there to say that it’s there.

Eric: [00:04:24] It’s a token in there to say you reduce the money. But like you say, that $100 reduction in Senate campaign caps is a little less than a 4 percent change.

Eric: [00:04:37] That’s not getting the money out of politics.

B.J.: [00:04:39] It’s largely not that meaningful. The majority of States Senate contributions are way below that anyway. Most people aren’t maxing out to a state Senate candidate or to state House candidate at this point. Some people are, but that’s just not the general gift. That’s not changing the typical process.

Eric: [00:04:57] Another thing you touched on too that I think a lot of people have tried to make this out to be that it has nothing to do with is getting rid of dark money. Those 501c4 organizations have gotten a lot of attention the past couple of years where they can spend unlimited amounts of money on political activities as long as they stay within some boundaries but don’t have to disclose their donors. How does this address that.

B.J.: [00:05:23] When I read through this I don’t see it addressed. It claims to be cleaning up dark money. I don’t see where dark money is removed from the process in any way. Additionally, we all know the campaign in favor of this has taken a lot of dark money. We don’t know where a lot of it’s come from because it comes from anonymous sources and third-party donors and that kind of thing. The claim has been made, but I don’t see where it changes anything regarding dark money.

Eric: [00:05:49] Another issue on there is that it would eliminate almost all the lobbyist gifts to General Assembly members.

B.J.: [00:05:54] This is a change that it would say that it eliminates gifts over, I believe $5 to individuals inside the General Assembly. It doesn’t eliminate gifts to the entire general assembly, so you can invite the entire House or the entire Senate or all to a banquet or to a dinner or to an event. Sometimes that’s actually taken advantage of knowing that only a couple are going to come you invite everybody and it becomes a group expenditure. There are some changes here. It would eliminate some gifts. Let’s give credit where it’s due. But it does not get rid of all gifts to the General Assembly. But it does make some changes here.

Eric: [00:06:29] This is one of the pieces in here that’s probably one of the better steps. But it is not a cure all.

B.J.: [00:06:35] Farm Bureau is by no means against that part.

Eric: [00:06:38] You also mentioned one of the issues that frankly I didn’t even know was still legal, was not allowing fundraising activities to happen on state property.

B.J.: [00:06:49] That’s a that’s a solution looking for a problem. There’s not a lot of fundraising going on on state property. I don’t know that there’s any to be honest with you. But just another one of those things that looks like it’s making a claim. And, it also helps push down what we believe to be the real agenda further down or what people read in the ballot.

Eric: [00:07:07] Then another one that really does have some impact but not as drastic as I think it’s been portrayed is that it would slow down the revolving door between people in the Legislature and then moving out to be a lobbyist. It extends the cooling off period that they have.

B.J.: [00:07:26] The current cooling off period is one year from from serving in the Legislature. This would extend that to two years. The troubling thing to me that it also adds is is legislative staff. I know a lot of people may not care about that, but there’s a lot of young people getting out of college going to work and they’re getting great experience there To tell them what they can and can’t do following that employment becomes pretty tough for me to settle on. But just the basics of we’re going to tell somebody what they can and can’t do not only for one year but for two. That seems like a stretch. We already have a one year cooling off period. I’m not against the two year cooling off period. I just don’t think it changes things as far as who’s coming from the Legislature and then going to work as a lobbyist if you’re going to wait one year you could probably wait two. You go to work in management and then get into you know government outlays .

Eric: [00:08:17] And that’s where I’ve seen that as an issue and kind of on the federal level as well. What that really does is just hurts the staff because they’re not going to get a special deal like.

[00:08:26] Oh no they’re not going to get that to hold your position for a couple years. And so that’s where it’s a major issue. It doesn’t change that much. It looks good it sounds good. We don’t disagree with the revolving door in cleaning up politics. I don’t know that this changes who does come from the Legislature to work in the Legislature.

Eric: [00:08:46] The last other issue aside from the redistricting is that it would require the legislative records be made open to the public that they would be if they come under the sunshine law in the same way that other administrative executive branch records are as well.

B.J.: [00:09:02] My my understanding and I’m by no means an expert on this one provision but my understanding is largely legislative records are open to the public. The one thing I will say is from what I understand most of the records that aren’t open to the public are because they’re for their personal information. It is a citizen from this person’s districts personal information that’s basically been excluded from the record or its constituent work done by legislators. That’s the kind of records that have been shut off to the public, because it’s your personal information. It may be your health information or your financial information. I have talked to some people that work in the capital that say this could be a real issue for them of what records they can keep and what records they can’t keep. Some of their files of issues they’ve worked on have always been considered their files, and to say that somebody could come in and really pilfer through for any political agenda. Let’s not sugarcoat this. Sometimes those sunshine requests are done for a political agenda and sometimes we want to make sure that private information should be kept private. Now, we’re not saying hide the works of government, but I don’t think that’s a major problem in our Capitol either.

Eric: [00:10:14] What my other concerns on this is that you are putting this requirement on state legislators.

Eric: [00:10:21] They basically, most of them, kind of do their own work. They have one assistant. Some of them they share an assistant across several people and to bog them down with having to respond to records requests all the time seems like a real waste of their time. You really could bury them in paperwork by putting this requests on them for a like you say a political agenda. I don’t see that really benefitting much, but it could cause a lot of harm.

B.J.: [00:10:49] I’ve also heard that for those working in the Capitol they would they would be asking for the assistance of someone with a law degree to decide what records could be kept and what shouldn’t be kept.

B.J.: [00:10:58] Almost every record would have to go through that sort of process. At this time our legislative staff don’t have that type of background or at least the majority of them don’t. This would be an extra burden on them or an extra hiring process for the capitol that could afford to pay people.

Eric: [00:11:16] That covers the main issues in Amendment 1 that are not part of the redistricting proposal. As a whole why are we taking the position that those aren’t really the strongest.

B.J.: [00:11:30] You know and I think that’s a great point.

B.J.: [00:11:33] There are a lot of things in there that we don’t disagree with the idea behind this. The selling point is that this is going to clean up politics. I think the changes are mostly window dressing at this point. You $100 on campaign contributions to state senators, one extra year of sitting out. These are just minor changes to mostly already existing policy. The other thing I would point out is these policies have gotten 90 percent of the way through passage through the Legislature. They have strong bipartisan support. If the people that support these would all have gotten behind those efforts in the Capitol we probably would have seen these get passed through. The truth is this could work its way through the political process in the state of Missouri rather than having to change the constitution. The problem I have with changing the constitution is then it’s so hard to change. By enshrining this in the Constitution it becomes very difficult to ever change.

B.J.: [00:12:28] Ultimately I don’t think these changes achieve the goal of cleaning up government. I think that we still see dark money issues. We still see people going from working in the Legislature to coming in and lobbying. I don’t think those are the major issues in the Capitol. There may be some issues that need to be addressed in the Capitol. I don’t think these do it.

B.J.: [00:12:48] We get to the meat of it which is the redistricting proposal, and I think as you are alluding to, if this were just put on the ballot on its own I think it would have real trouble passing because of problems with it. That is why they tack all these token other things onto it is to try and make it look like a real true overall comprehensive reform of government.

B.J.: [00:13:10] If you were signing a petition, if you’re walking out of Wal-Mart and somebody says do you want to clean up government, sign this. It was pretty easy to gather a signature I imagine.

Eric: [00:13:17] Absolutely. But on the redistricting itself how does that plan work, and if this were to pass who would get to decide how those districts are drawn.

B.J.: [00:13:28] A new state demographer is charged with drawing competitive districts around the state of Missouri. That demographers chosen by the state auditor, the auditor choose his candidates and then the majority and minority leaders in the Senate can narrow that list. So, supposedly it has to be kind of in thirds. They could remove one third and the other third and then there would be a couple candidates left.

B.J.: [00:13:52] It would go up to it could possibly go to a lottery of the remaining candidates.

Eric: [00:13:57] But ultimately, the only candidates at all would be people that the auditor put on the list.

B.J.: [00:14:03] The whole list never expands. If I was a partisan leaning one way or the other I could put four or five extreme partisans and both minority parties could just say well we don’t like one in two but we really don’t like the ones in the middle either. And then it goes to a lottery of the people they don’t like anyway. So yes, ultimately the auditors position will decide who the state demographer would be if this were to pass. And then demographers charged with drawing competitive districts across the state of Missouri and competitiveness is measured by what they call wasted votes. Now I was always taught that no vote was wasted. No wasted votes or any vote for the losing candidate or votes above 50 percent that’s necessary to win. And so they would have to go around the state, assume that they know how everybody is going to vote based on how they voted previously, and then try to draw competitive districts. That’s where we really see an issue. Populations of the state of the Missouri. We see if you look at the map of red and blue, the truth is that the urban centers have more blue at this point. They haven’t always. That’s the one thing I like to stress and this is voting patterns change over time. This assumes everybody’s going to vote the same way they did two years ago, the same way they did eight years ago. I personally don’t. I know a lot of people who don’t. And so I think that it’s interesting that they want to try to think that they can enshrine how we’re going to vote. The truth is if you look at red and blue, the urban centers — St. Louis, Kansas City, Springfield, Columbia — where largely populated areas are in closer proximity. Those tend to have more Democrat leaning voters. This demographer will have to try to draw districts that dip in and receive enough of those urban center voters and enough rural voters who have recently been leaning Republican in order to find a competitive district and competitiveness.

Eric: [00:15:57] That’s really the most interesting thing about this proposal because it’s unique nationally this would be the first time it’s really been tried to force your districts to be based on partisan voting patterns. This would be not about trying to make things fair but trying to make things partisan balanced.

Eric: [00:16:14] And it’s only between two parties, the Republican party and the Democrat party, that completely leaves out other parties at parties.

Eric: [00:16:19] If you’re a supporter of a third party or if you’re an independent, you don’t really get considered. It’s about Democrats and Republicans and only those two parties trying to be balanced across the state.

B.J.: [00:16:31] Our current bipartisan commission that comes together that draws districts is charged with drawing them compact and contiguous, meaning they’re supposed to keep communities of interest together. They are supposed to keep counties together. They can’t cut through cities or counties unless they absolutely have to. So, you see a map that largely makes sense. Northeast Missouri is represented by northeast Missouri. Same thing with the different regions of the state. The urban centers get divided because they have more people. There’s only a hundred and something thousand in the Senate district, but where they don’t have to cross a population line they don’t.

Eric: [00:17:08] That’s actually one of the questions or comments we’ve been getting a lot on social media. People are saying the current map is really badly gerrymandered.

Eric: [00:17:17] So, does this proposal get rid of gerrymandering because that’s how it’s been pitched I think by the proponents of it.

B.J.: [00:17:22] Gerrymandering is rampant in the state. The truth is when you draw lines you always have to put them somewhere. I took a look at the Missouri Senate map, the current map, and that does that’s not to say that this map is perfect. The current Senate map divides five counties and that’s where you would think they would be.

B.J.: [00:17:48] Green County, the city of Springfield is one, outside is another. Jackson, Clay. St. Louis and St. Charles, the county of Jefferson. That’s where you see the dividing lines now. It just makes sense. Counties are kept together. You may not like that you’re divided from the county. You may think you are more similar to Scott County than Perry County or whatever, but lines always have to be drawn. But currently, we keep those counties together as much as possible or the commission does as much as possible. State House seats are tougher because they’re smaller districts, but typically gerrymandering is minimal. Not everybody agrees with where the map is, but the process allows more. If they don’t like the map they can contest it in court and the courts decide whether or not these were fairly drawn, not fair as far as any party can win.

B.J.: [00:18:37] But fair as far as this district makes sense it’s compact and contiguous.

Eric: [00:18:40] That also plays into the next question that we’ve been getting a lot, which is what Farm Bureau has been saying, that this amendment would silence rural voices. People are saying well how would it? They would still get to vote. Why would this redistricting proposal actually hurt any rural voter.

B.J.: [00:19:04] I think this is a good time to show, and hopefully we’ll be able to show on the Facebook Live or the Facebook video the actual map closer. Eric and I are looking at a map that was drawn. This isn’t what would be the map, but it’s an example drawn for competitiveness where they drive to draw as many 50-50 districts as they could.

Eric: [00:19:25] The group that is opposing Clean Missouri hired a demographer to draw up a map based on the guidelines that are in Clean Missouri and said “Can you come up with a map that would fit these guidelines to the best of your ability.”.

B.J.: [00:19:39] And my understanding is they charged them to be fair, but to draw with these understandings and not to try to be too extreme but I try to be fair.

B.J.: [00:19:48] When you look at this map, and I do think that some of them are probably more extreme than others, but we can see several districts where you’re dipping down into St. Louis City and then running all the way to half of Randolph County. I think we’re going from the district that’s labeled as 20 is going all the way down into Ferguson and then including northern Columbia. That is a huge district, and that’s where we get into what we see as a real issue. It’s an issue for rural Missourians because we’re more spread out. If I was campaigning in District 20 I would have to spend more time where there’s more voters concentrated. I wouldn’t be able to spend a lot of time in Warren and Callaway County because there’s not as many voices there. I’m going to have to spend in Boone County and Callaway and I just think that leads to rural Missouri having fewer voices in the Capitol just because people are going to gravitate to where the population is most densely populated. When we talk about real representation in the Capitol, we’re already somewhat of a minority of agriculturalists or people from rural portions of Missouri. I think that just dilutes us. We talk a lot about agriculture and there’s only 2 percent of the population that’s involved in agriculture. And we just want to make sure that rural voices continue to be heard. I think as we try to divide these districts or draw them along competitiveness lines, if every district has to involve a rural or an urban center we’re going to see a large divide in that. I think we’ve seen that echoed from our urban counterparts that say we want urban voices in the Legislature and they say okay, if you have a district that goes all the way from inner city Kansas City, you say Kemper Arena, all the way to Linn County, they don’t like that district either because they want to ensure that they have their voices heard too. They don’t feel comfortable knowing that someone from Davies and Linn and Caldwell County are going to have their best interest in mind. I totally understand that. I think it also would be next to impossible to represent these district. If you’re representing 20 school districts and four counties, it’s hard to know which voice you’re supposed to be speaking for.

B.J.: [00:22:01] It’s going to be very difficult for anybody to represent.

Eric: [00:22:04] Like you mentioned, the example district number 20, which is the blue district in east central Missouri. It goes all the way down into Ferguson, the Jennings area, almost all the way to the Mississippi River, and then comes out all the way through Warren County, Callaway County, Audrain County, Boone County to try to get that balance between Democratic voters and Republican voters. Just imagine if you were the senator from there and a bill on education came up, would you be voting based on what the people in Ferguson and Jennings wanted or what the people in Audrain County or Boone County or what. I mean how in the world would you know.

B.J.: [00:22:43] I think it would be next to impossible to choose, and I’m not trying to be rude to those legislators but what do you do. I think that would be very very difficult for anybody. The other thing that you mentioned one of the last times we talked about this was about people knowing their Legislature and the importance of that. I don’t think that can be undersold here. A lot of our folks, whether they be urban or rural, they know who their representatives are, they know who their senators are. He or she may not be from their city or their county but they’re familiar with them because they know they speak for their county. I know firsthand I’ve spoken with Farm Bureau members from a county that’s divided three ways. You know from the outside looking in you think that’s great, your county has three representatives and they feel like their county has no representative because there’s not one representative who owns that county, who speaks up for them on a continual basis. Not to speak negatively towards any representative or senator, but that personal touch really is important to people.

B.J.: [00:23:43] It helps with your relationship in the Capitol. We want to make sure that we continue to protect that. Missouri has issues in the Capitol. Not everything’s perfect. We have seen some dirty things happen in the past. Our track record isn’t perfect, but it’s not the dirtiest state, and by any means, but I don’t think that this proposal and this redistricting is to try to clean things up.

B.J.: [00:24:07] I think this is to try to change the status of the Legislature.

Eric: [00:24:12] Its an effort to try to win more seats in the Legislature when you put one them at the ballot box. That’s what it really comes down to. This would not be your proposal if your ultimate goal was getting a cleaner process. You did mention that there is an issue where people who are in areas that their district, that their town, is split up in multiple areas or multiple districts contact their congressmen less, contact their representative less, because they don’t know who they are. They just are less civically engaged. And that’s one of the problems with gerrymandering in general and gerrymandering for political partisanship is the worst kind of gerrymandering.

B.J.: [00:24:59] There could be a claim that that’s what’s been done in the past. This constitutes it. It says you have to gerrymander for partisan races.

Eric: [00:25:08] So that goes to our last question. We’ve gotten some questions about on social media that what are some of the constitutional issues with Amendment 1? We’ve mentioned that a little bit that the two parties are just enshrined in the Constitution that now the maps are drawn for their two benefits and you forget about all the third parties. That’s something that Senator Jim Talent who is the main spokesman opposed to Amendment 1 brought up on our podcast when he spoke with our President Blake Hurst. He feels like that’s completely unconstitutional because the Republican Party and the Democrat Party are not governmental entities but private groups.

B.J.: [00:25:49] There is nothing that says that in 5, 10, 20 years from now that that’s not the process we lean towards. That there’s not just two parties. There’s always the possibility of a third party or independents. This would alienate those and make it even more difficult. I think if you’re coming into what is drawn as a 50/50 district and trying to pull 2 percent of that, that becomes very difficult. I mean next to impossible.

Eric: [00:26:15] And then you also mentioned some of the issues that some people are concerned about in their urban communities they are required by the Voting Rights Act to have a majority-minority district. I think there is a lot of leaders in those areas that are concerned about how this could impact that. The proposal does explicitly say that you do still have to protect those districts under the Voting Rights Act. What a lot of people are concerned about is it would dilute the percentages in those areas. If there is, say a Democratic district that’s heavily African-American or heavily minority and in typically a Democrat draws 70 percent of the vote, now, this might draw down to where they only draw 55 percent of the vote and they could lose a lot of seats that way too.

B.J.: [00:27:01] It has to, and that’s where it really gets into what provisions of this override other provisions of this. That’s where I think it becomes next to impossible to really enforce and to draw districts this way. Another thing I think is important to point out is there are several states that are trying to go to a bipartisan commission to draw districts the way we currently use. Missouri is actually seen as a leader in how we draw our districts because we bring a bipartisan commission of people who can’t have been involved in the Legislature for several years. They come together to draw the districts and then they present them to the Legislature for their adoption. Sure there’s some politics to it. There is always going to be politics when you’re drawing legislative districts that’s just a fact. But this makes politics above anything the most important thing is the whole point of this.

Eric: [00:27:50] That’s exactly what this is trying to do is involve politics as the only thing that matters, which is exactly the wrong direction to be going. I appreciate you taking some time to run through these. Anything else we need to go.

B.J.: [00:28:03] Yeah I think we probably ran a little long. The one thing I want to close in saying is I think that some of the things that Clean Missouri claims to do to clean up Missouri aren’t worth what it does to our redistricting process. The pain that this will cause to rural voters, to urban voters, far outweighs any good that could come from the clean up of things they say they’re going to do. And furthermore, the issues that they would like to see get done could be done through the Legislature. Not the redistricting portion, but portions could get done through the Legislature. We’ve seen movement on them in recent years and I truly believe if the proponents of this would all come together and push for these changes we would see them pass the Legislature.

Eric: [00:28:43] So get out there on Tuesday and vote. Let’s vote this thing down and come back with some actual real proposals next time around and do it the right way. Vote no on one. We have some other issues that we’re going to be talking to you about.

Eric: [00:28:56] You can also get some information on Q and A’s about Proposition D. B.J. and I did a video about that as well. Check those out so that you can see what you’re gonna be voting on on Tuesday, but most importantly get out there and vote. Rural voices are going to make a difference in this year’s election. Don’t miss your chance to make your voice heard. Thanks for joining us.